A Reflection for The United Church of Hinesburg: Rev. Baybie Hoover & Virginia Brown

(Insert audio clip invocation :28 sec.)

In 1976, I met a blind Manhattan street singer named Reverend Baybie Hoover and her Deaconess of Music, Virginia Brown.

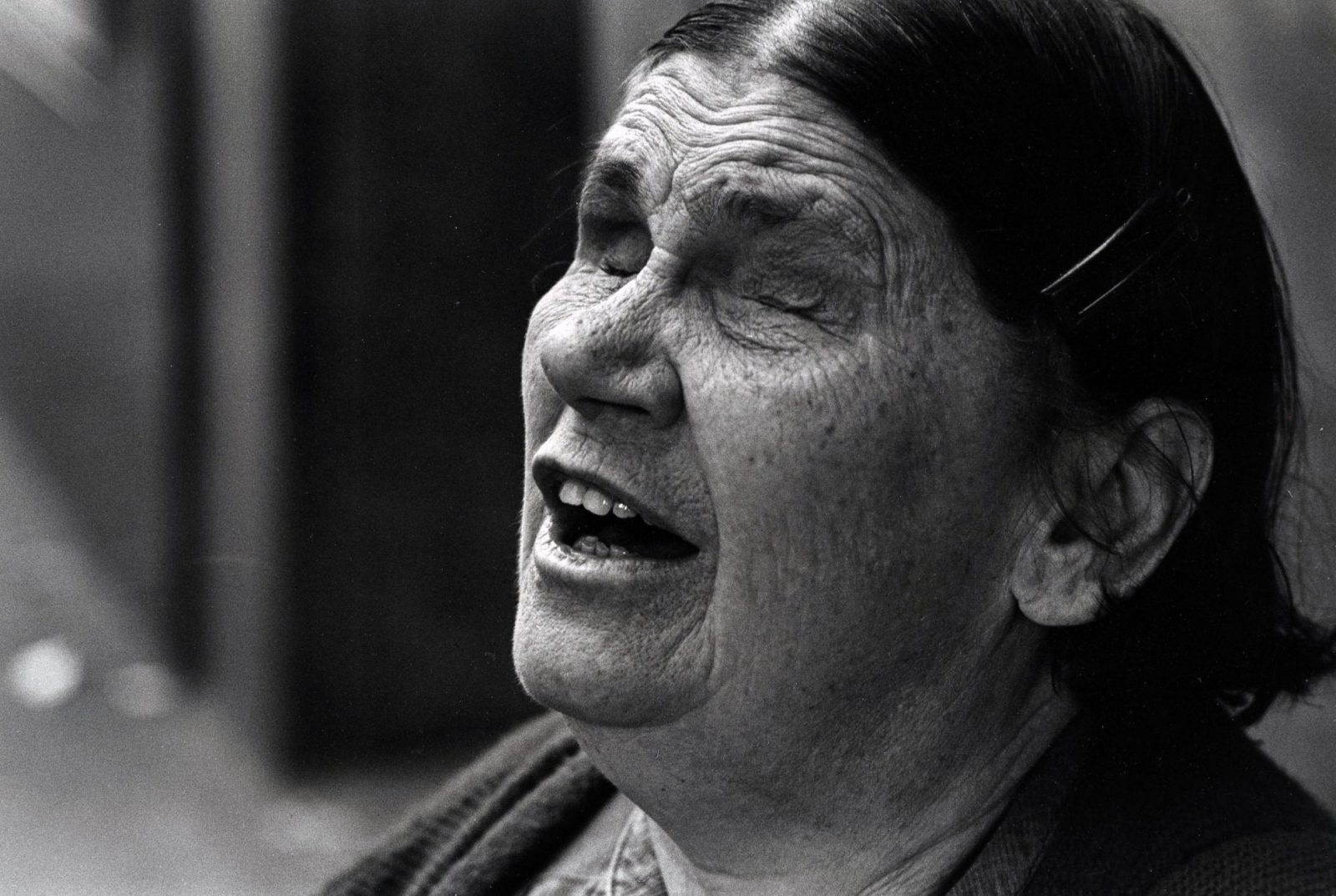

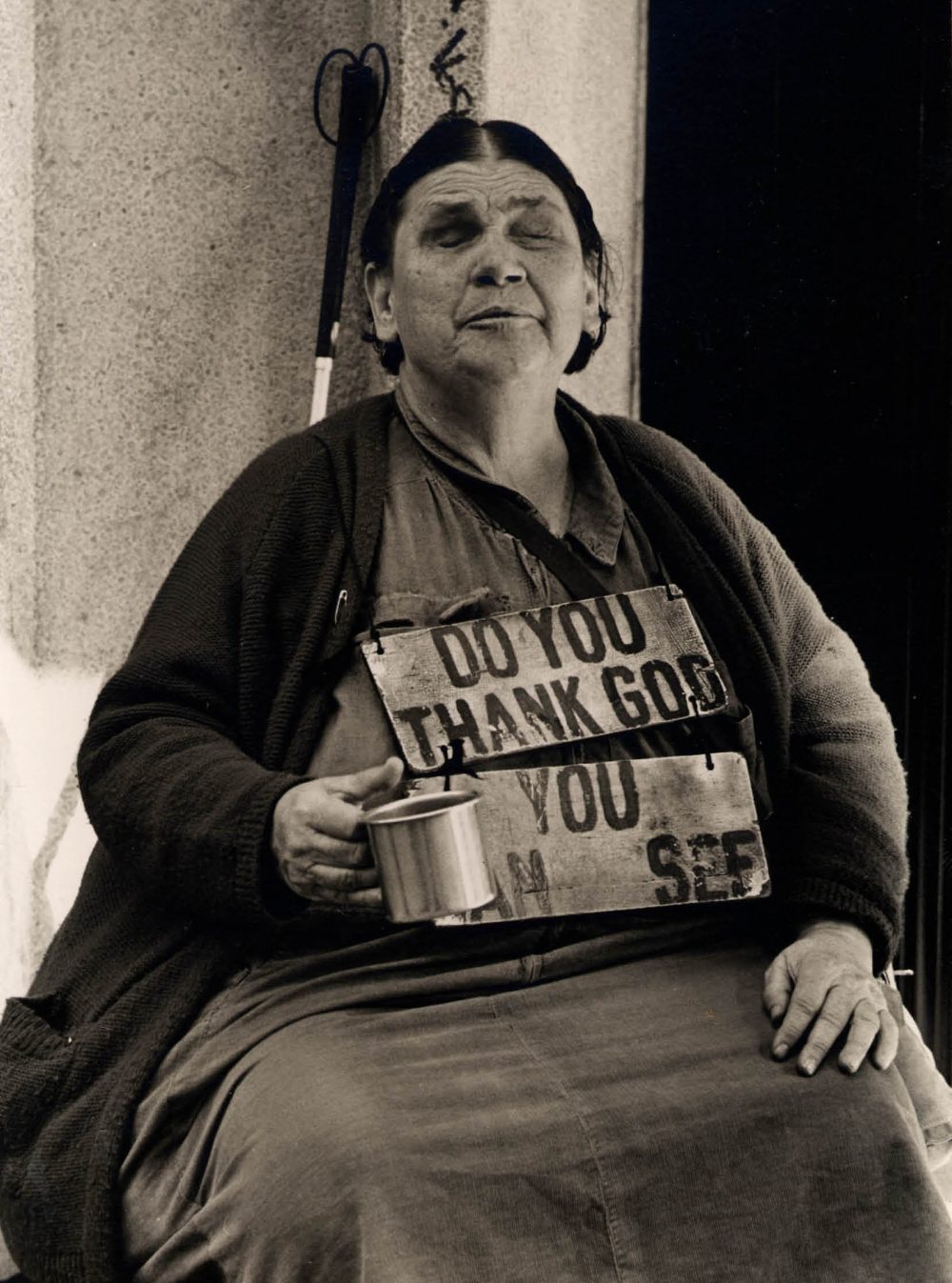

Rev. Baybie Hoover busking at Bloomingdales – 1975

Baybie’s early life was marked by a succession of tragedies. She was blinded at birth by a drunken doctor called to stem her mother’s hemorrhage immediately after her birth. Sexually transmitted diseases were the norm at that time as was the practice of rinsing out a newborn’s eyes with boric acid solution to eliminate any infection picked up in the birth canal. In his inebriated state, the doctor grabbed the vial of acid he kept in his bag to sterilize hypodermics and accidentally blinded the newborn Nadine Hoover. When he realized what he had done, he then said to the half-conscious mother that he was sorry but her baby was born blind and he left.

Her alcoholic father abandoned his wife and new daughter. Baybie’s mother died 18 months later of pneumonia and Baybie was remanded to the Kansas City School for the Blind where she first learned music, one of the few career options then open to the blind.

At fourteen she was fostered out to a farm family in remote Kansas and sent alone by train to Wakeeny, Kansas with a note pinned to her dress saying she was to be picked up by Elroy and Hetty Desmets.

That winter she was molested by her foster father impregnating her at 14. Her foster mother blamed Baybie for “vamping” her husband and the young Nadine was taken into custody and remanded into the care of the Briller Maternity Lying-in Home in Topeka. There she was treated well and made friends.

When her time came to deliver her baby, she was removed to another building and gave birth. Girls were never told that their babies would be taken and sold into adoption and many, including Baybie, looked forward to being mothers. She might never have known the sex of her baby had not a kindly nurse whispered to her that she had delivered a beautiful baby girl. When asked to see and hold her, she was told the baby was gone and would be adopted. The delivery doctor came to see her afterwards as she was crying and informed her that he had “fixed her so she wouldn’t have any more kids” expecting gratitude. Baybie lived with this heartbreak all her life.

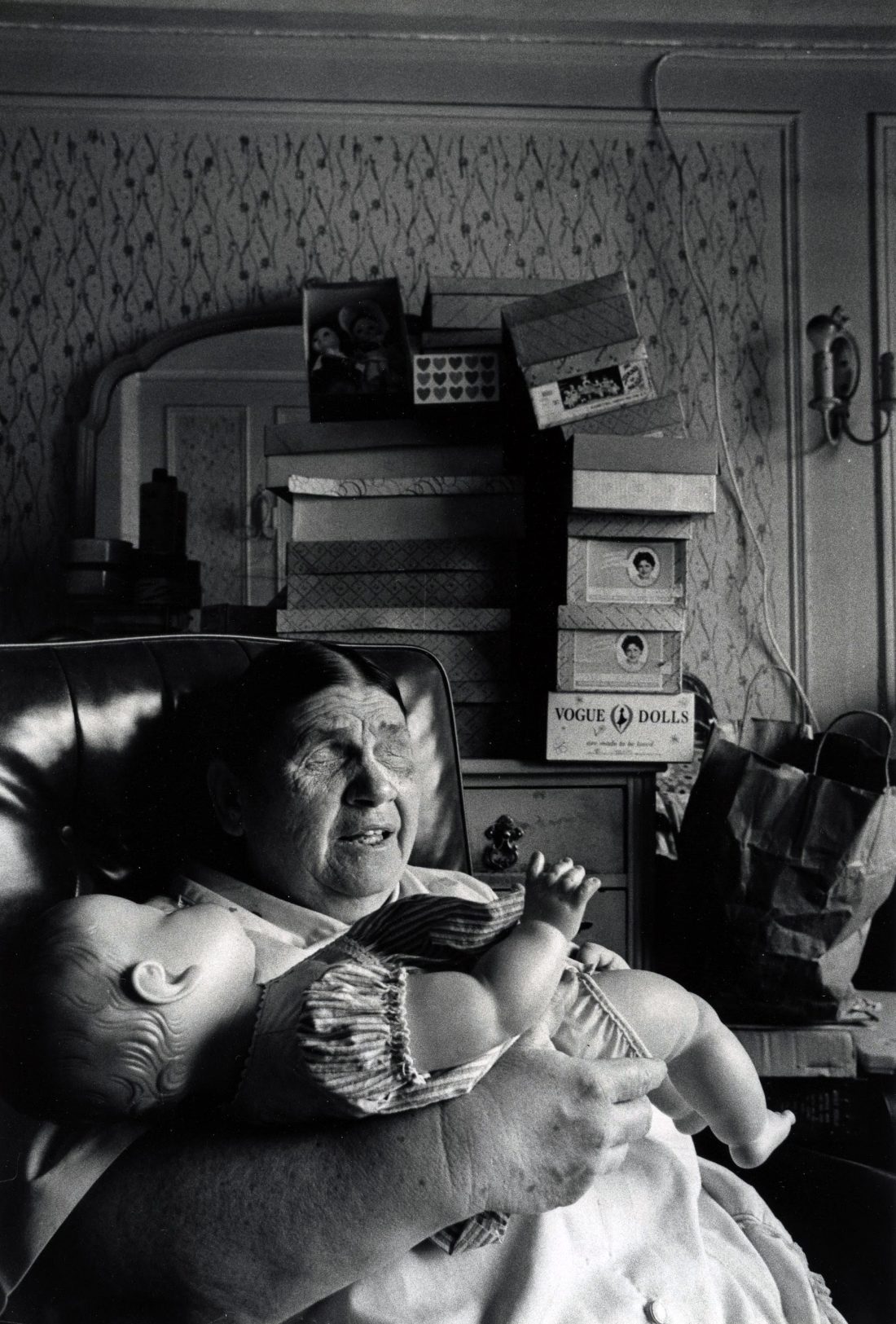

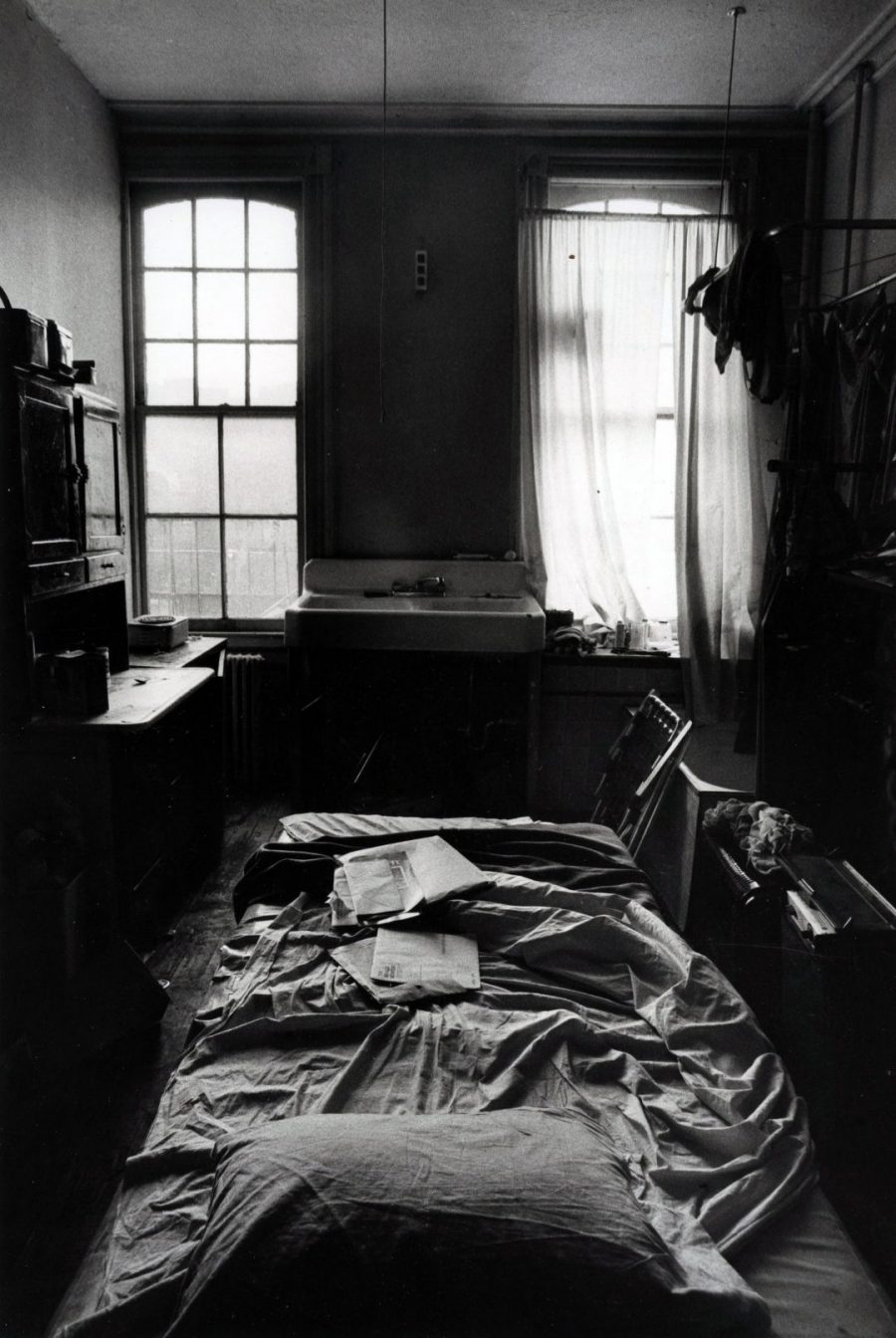

When I knew her, Baybie lived in a single-room-occupancy (SRO) in midtown Manhattan in The Markwell Hotel and every day, rain or shine, she made the subway trip to the Upper East Side to spend the whole day singing with Virginia on the sidewalk under the Bloomingdales entrance awning.

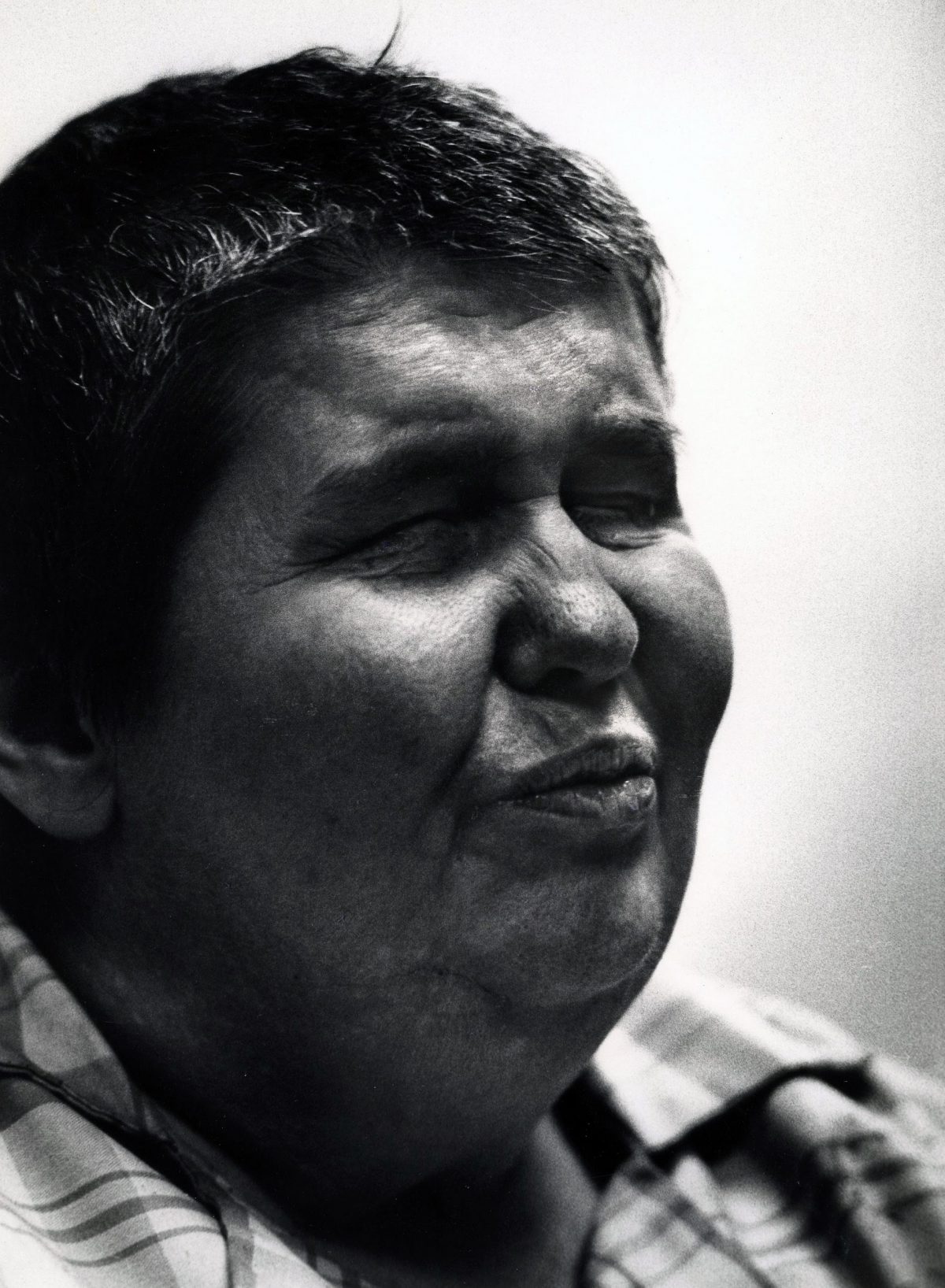

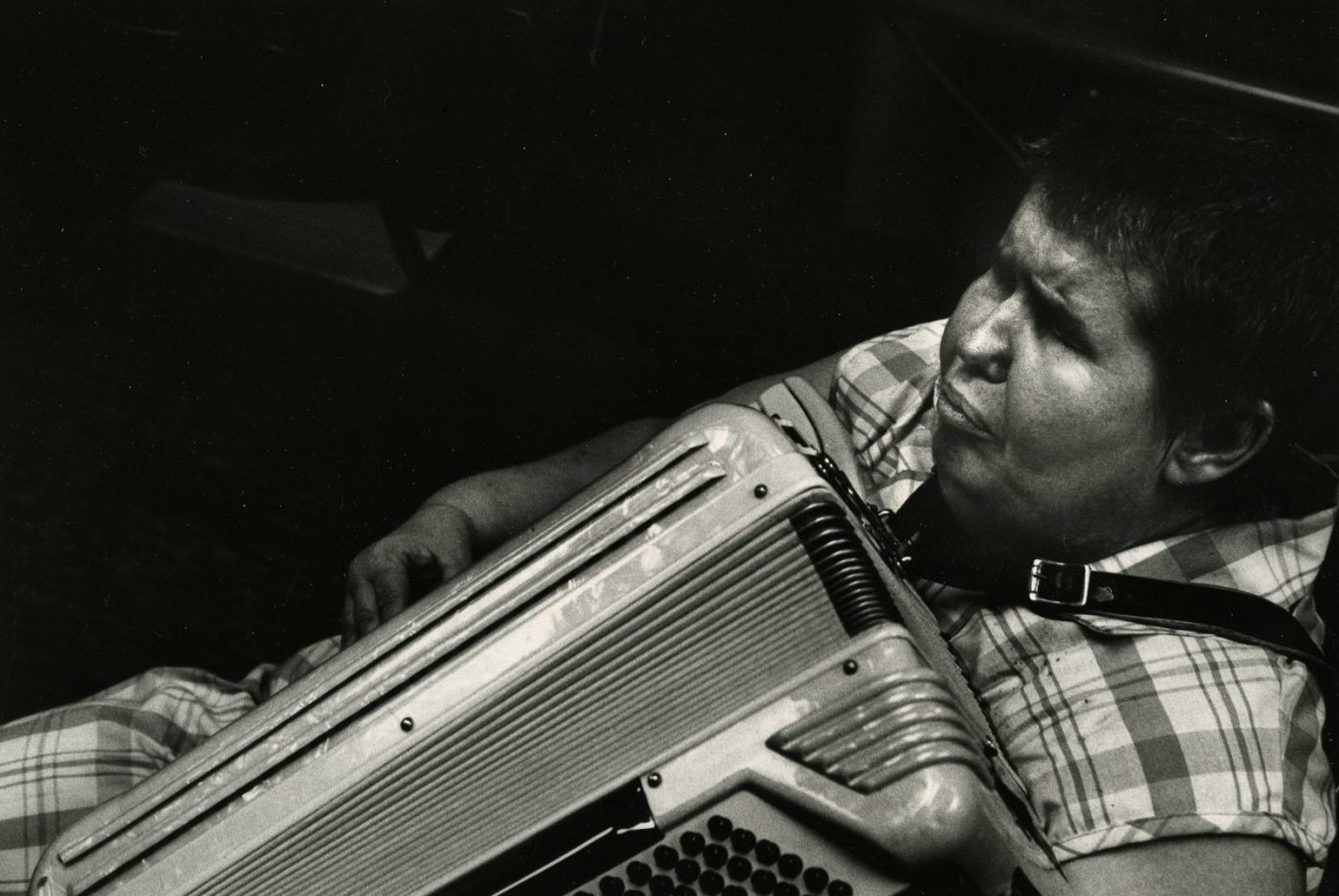

Virginia Brown, Baybie Hoover’s deaconess of music

My partner and brother, Mike Couture and I decided to produced an album (Philo 1019) of Baybie and Virginia’s extraordinary songs and harmonies, during which time we came to know her and were captivated by her extraordinary personality.

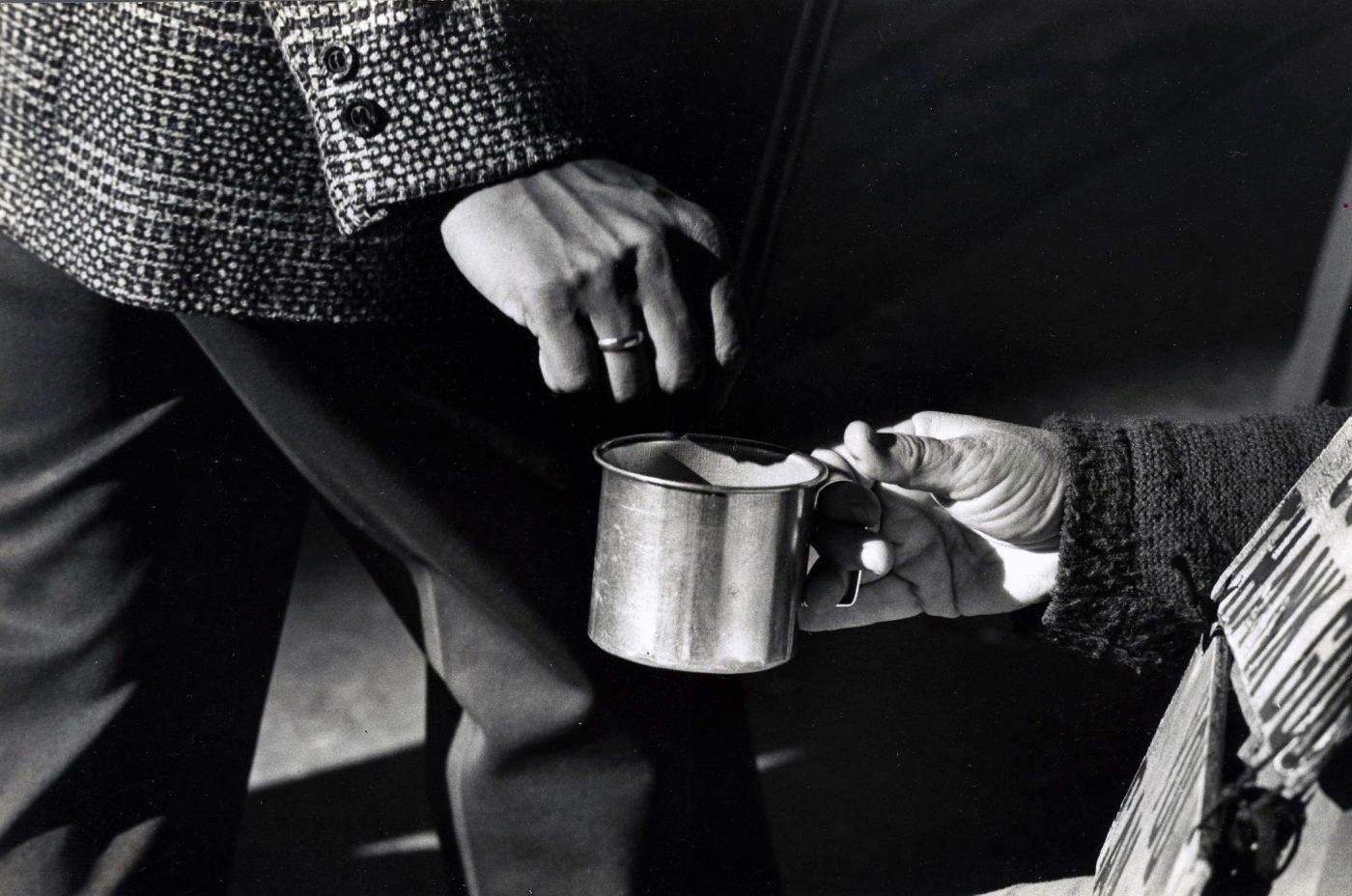

The Rev. Baybie Hoover accepting payment for her singing

Insert: You Had Better Dig Deeper song

Rev. Baybie Hoover

At her invitation, I visited her room in the Markwell Hotel on West 49th St off Broadway. I was struck by the large collection of dolls Baybie had on her dresser. Noticing my confusion, she told me that they were the little girl that had been taken from her and she felt great comfort caring for them.

The following Sunday, Baybie invited me to her church service in an abandoned building in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, an area at that time that saw few, if any, white people. The Manhattan cab driver did a double-take when I gave him the address. There I found an abandoned house with concrete steps leading down to a basement, which was Baybie and Virginia’s Church.

There were six of Baybie’s faithful, all blind like her and Virginia sitting in folding chairs. Baybie asked if I would get the donuts out of a cupboard and put them on a plate to serve. After chasing away a hoard of cockroaches, I arranged and served the donuts and Baybie began a service that is among the most memorable spiritual events I’ve ever been part of.

After some group singing, she rose to a homemade lectern and delivered a sermon on gratitude. There was little in Baybie’s tragic life that I had heard that warranted this gratitude, yet she spoke movingly of all the people in her life and especially of those who had been kind to her and Virginia.

Mike and I eventually produced the album (Philo 1019) with braille liner notes of “The Rev. Baybie Baybie Hoover and and Virginia Brown.” When the albums were manufactured, I brought a couple of boxes to New York to give to Baybie to sell on the street. I invited her and Virginia to dinner to celebrate the release of her record and told her to pick any restaurant she wanted. There was an Italian restaurant off Broadway where Baybie and Virginia went after work to pick up leftover food from the kitchen. Their friend Aldo who worked in the kitchen each night put together a foil plate of leftovers that he handed Baybie when she knocked at the door in the side alley. Baybie said she would like us to go there to celebrate and when we got there, asked that I take her and Virginia’s arms and escort them in through the front door which they had never used. We made a grand entrance. Clearly many of the wait staff knew Baybie and Virgnia as they surrounded us while she showed off her new record. Aldo came out from the kitchen to share in the celebration. As if by tradition, no bill ever arrived after our meal.

Rev. Baybie Hoover 1976

Baybie was a woman who had few, if any, reasons to be grateful. Yet she lived in a state of perpetual gratitude for what little she had. She rarely indulged in any judgment of those visiting misery on her. I had never met anyone who saw life and the people she encountered with such generosity of spirit. Just being in her company made me ashamed of every complaint I had ever uttered and, only in putting her life’s story in writing, could I ever hope to fully recall the grace and gratitude this woman brought into my own easy life.

(1004 words)