Our Communities, Our Schools, Our Children

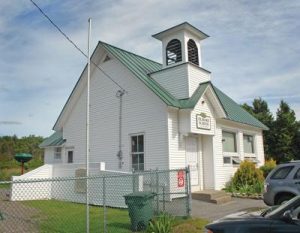

Elmore Town School: VT Community Newspaper Group

I recently led a discussion at the Elder College, a life-long learning division of Elderly Services in Middlebury. I’ve led many classes and discussions there since my own retirement. I do so because it’s an opportunity to learn from my peers.

Our most recent exploration focused on key indicators and metrics one might use to assess the well-being of our communities.

Here is what our team came up with:

(1) Participatory culture and governance policy: i.e. residents believe they are equal, integral, and formative parts of their town and come together to:

- debate and make important decisions (e.g. about town buildings, library, taxes, school and public safety budgets, community center, gym, sidewalks, etc.) (Australian ballot replaces Town Meeting)

- volunteer their unique service contributions to their towns (e.g., coaching, mentoring, reading, serving on fire department, community gardens, clean-up).

(2) Employment & service opportunities

(3) Quality of educational system and access to life-long learning

(4) Quality and access to affordable health and childcare

(5) Safety of community and physical environment

(6) Diversities: gender, race, religious/spiritual, age, economic, sexuality

(7) Social and cultural fabric – recreation, arts, parks, cafes, shared gathering places, senior centers, bike lanes

While we might have debated the relative importance of each, this order distilled our combined work. We might call these the social determinants of community wellness. In my last column, I discussed the social determinants of citizen wellbeing.

As our urban centers expand and our smaller communities shrink and lose their local schools, their local papers, their sole-practitioner doctors, their general stores and specialty shops, and as they struggle to support their local fire, emergency medical services(EMS) and police services with a shrinking tax base and try to clear, patch, and grade back-country roads, we risk losing the very character of the Vermont that is most attractive to visitors and newcomers.

In the ‘50s, my hometown, Morrisville, with its population of some 3000, had a vibrant downtown filled with people and shops. We had two movie theaters, two grocery stores, a jewelry store, news stand-tobacconist, three pharmacies (each with a soda fountain), three dry-goods stores, a post office, two gas stations, a rambling building supply store, a hardware store, appliance store, and two taxi companies and the two-story wood frame Randall Hotel with its wraparound porch and rocking chairs. We also had a 150-year-old primary school and academy (high school) and in the ‘50s built a middle school.

Today, Morrisville has several cafes and small restaurants, three chain gas stations/convenience stores, a chain pharmacy and grocery store, an outdoor gear shop, a cultural center and a movie theater and its three schools.

It’s often said in migratory studies that chief among family and business relocation priorities is quality of education ̶ access, affordability, and quality. If education is indeed vital to personal and community well-being, why do we pay it such short shrift, even as we pump more and more money into it?

I went to kindergarten and grade-school in Morrisville for nine years. My teachers were, with one exception, women who cared little about my self-esteem, but focused on my capacity to learn. I feared and respected them and wanted to succeed in their classrooms. They were kind and humane but did not seek my approval on all their decisions.

At thirteen, I went away to boarding school, not because of my brilliance but because my biological father, who died before I was born in the Pacific theater, had gone there. I struggled at Exeter at first but was sustained by a solid grounding in the prerequisites I had gotten from the women who taught me back home. In my second year I got a B- on a paper and was so excited I spent a chunk of my monthly allowance to phone home.

Meeting with a college-educator friend who had taken an interest in our foreign exchange student going to CVU, she asked her how she was doing. We were all taken aback to hear her answer that she is getting a 4.3 G.P.A. We had assumed that the range was 0-4. It was like getting 110% on an exam. Our student gets three A+s and two A’s. We knew she was doing well but were stunned to find that she was being graded better than perfect.

In Morrisville, grades were A-excellent, B-good, C-average, D-poor and F-failing. Students were held back until they received passing grades. There was no “social advancement.”

The system was not perfect and did not necessarily accommodate variances in child development, especially the considerable difference between the development of the prefrontal cortex in boys and girls. For that reason, girls were generally better performers in our school system than boys. Of course at Exeter in 1958, girls need not apply.

We are in our 70s and our foreign exchange students have been in their mid-to-late teens. They’ve both come from economically struggling Eastern European countries and neither came from privilege. Both are at least trilingual (most Vermont schools no longer have a foreign language requirement) and have been underwhelmed by the lack of educational rigor they’ve experienced here.

Our student from Moldova three years back said that the students interested in learning sat close to the teacher. The next group wore ear buds and watched their cellphones, which are allowed in the classroom. The furthest back often carried on conversations while the teacher taught.

Our latest student noted over dinner one night that a student in her class, when called upon to answer a question, looked at the teacher and said simply, “I don’t want to.”

I worry that our obsession with keeping our children “happy” and denying our parental obligation to raise and educate resilient, independent adults to perpetuate democracy and the human race is playing too large a role in the culture of our local schools and subsequently in the mental-health crisis affecting our young people.

There is indeed enough to disturb us all in this world, but hasn’t there always been? I remember the “existential dread” I experienced during the Cuban missile crisis when I decided to hitchhike home from Exeter so I could be with my parents when the nuclear bomb hit Plattsburgh Air Force Base.

If quality education is a driver of community and citizen wellbeing, we have work to do. We need to look at what we teach ̶ pedagogy and content when we teach ̶ age-informed by what we know about early childhood development and, finally, the culture of our classrooms ̶ remembering that we cannot instill a sense of self-worth, as that comes from self-awareness of accomplishment not from phony accolades or inflated grades.

We need to rethink our school systems, with a focus on the role they play in the well-being of our small towns and how they prepare succeeding generations for a complex and ever-changing world.

We can and must do better for our communities and our children.