The Correctional Facility

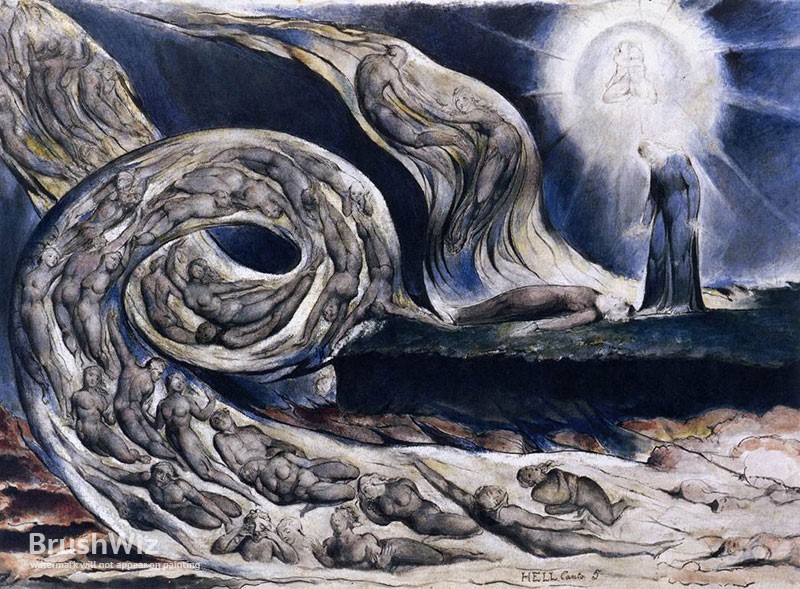

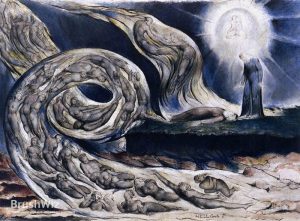

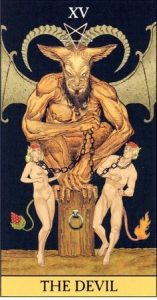

The Correctional Facility is an illustrated novella updating Dante Alighieri’s 700-year-old classic The Inferno. Our guide however is not Virgil but Walt Whitman and Dante’s flaming pits are succeeded by modern brutalist prison architecture. Many of the sins of Dante’s time persist today, but mankind has scaled old ones and added new ones. Invention, technology, economics, and politics have nuanced and scaled our concept of evil.

A novella by Bill Schubart

Illustrations by: Jeff Danziger

Editor: Chris Noel

Scheduled: January 2020 release

Magic Hill publishing / Ingram Dist.

Table of Contents

Canto I: The Boreal Forest

Canto II: Finisterra, the River Styx

Canto III: The Corrections

Canto IV: Falsifiers and Cozeners

Canto V: The Sexual Aggressors

Canto VI: Avarice and Greed

Canto VII: Homicides and Poisoners

Canto VIII: Racists and Bigots

Canto IX: The Garden of Innocents

Canto X: Lethe

Canto XI: Petrichor

From Canto II, Finisterra, The River Styx

“Time to board the ferry, Charon’s here in all his or her glory. I’ve never known which — a hermaphrodite, I’m told.”

Opening my eyes, I see no boatman, only a floating wooden platform with two swaybacked horses tethered at either end of a capstan wrapped a thick rope, both ends of which disappear under the roiling waters. Although I cannot yet see him, my guide points out to me how Charon switches the horses into action with his withe, and how, as they walk slowly around the circumference of their tether, the rope is gathered on one side and paid out on the other, drawing the ferry to the far shore.

Someone of nondescript sex steps from the far side of the ferry into view. I gasp audibly as my guide smiles.

“No need to greet Charon — her tongue is cleft and she can’t speak — nor to be afraid of him. He’s not as horrible as she appears. She confines herself to navigating the condemned across the river to the River Acheron that no longer exists — an arroyo now, desiccated by your ignorance, greed, and the relentless pollution that’s overheated our earthly paradise. You’ve so damaged my beloved home in the intervening years since I walked its majestic forests and fields.”

I’m transfixed by Charon, unaware of my rude stare. She — or he — seems not to notice me but goes about the business of guiding the ferry to the shoreline. She dangles her long withe in front of one of the horses and it stops, causing the other to stop as well. She then tosses a rope to my guide, who pulls the ferry up snug against the river’s bank so we might board.

I’m still staring at Charon, whose fulsome breasts, blood-red aureoles, and alert nipples hang free above his codpiece-covered groin. He has the torso and musculature of a man, and a thick pelt of simian hair covers his bare chest, arms and legs. More perplexing is the faintly seductive glance as she acknowledges her two passengers. Her distinctive face of indeterminate sex seems unravaged by the withering effects of ancient age, her faint smile rendered wry by the slight distortion of her mouth, no doubt from the cleft in her tongue. She says nothing but extends a hand to my guide to help him board her ferry, and then to me. As a young person I was taught to be polite, an attribute that has served me well all my life, but now I toss my pack up on the deck and clamber aboard the ferry on my own, ignoring the calloused, hairy hand Charon extends to me.

As my guide and I settle ourselves on the planks, Charon reverses the two sad rocinantes in their traces so they might walk clockwise around the capstan and switch the ferry’s direction to return to the far side. A touch of his withe on the flank of one of the horses begins the slow rotation again, and the capstan winds the dripping rope around itself from the river side and plays it out the shore side, as the ferry begins its slow traverse. The steaming water wrung from the thick rope runs across the deck in a rivulet that touches my hand, and I’m surprised by how hot the water is, even though I was warned. Soon we’re surrounded by a cold mist and can see neither shore.

From Canto III, The Correctional Facility:

We enter the hallway, leaving behind the cloud-filtered daylight, now replaced with a cold, bluish-white light infused from an invisible source in the ceiling. I look for anything indicating we’re in a prison.

“Where are the guards?” I ask.

“No need for any. Where’s anyone going to go except inside this building? It extends forever. There’s no outside. Nature’s gone – the endgame of man’s relentless destruction. There is no landscape, no wilderness like the one that fed and sheltered us on our journey here. The tenants in here are deprived of all distractions from their work of atonement, nor can they retrace their steps on the journey from Earth to this place without first purging all memory in Lethe’s spring. Even if one could find his or her way back to the river, Charon doesn’t ferry souls in that direction.

“Unlike in Dante’s time, this is not a place of physical pain. The 108 billion tortured souls who’ve passed through here in the last 50,000 years can’t imagine escape. It’s a correctional facility, and they have work to do and an eternity to do it in should they need it.

“Souls in here reside in groups according to their earthly sins. They’re ephemera – souls with bodies – but their bodies have no substance. Freed finally from the physical pain of living and dying, their only pastime is walking conversation. You’ll see no places to sit or lie down. They need no rest or sleep. There’s no cafeteria, no infirmary, no sanitary facilities. There’s no need to attend to the body, only to cultivate remorse and redemption.

Some spend centuries in self-justification or denial… a defensive response to the pain of guilt. Their redemptive path becomes clear as they begin to understand and acknowledge their sins, their guilt, and learn to empathize with their absent victims. Their infinite conversations with their peer sinners in time lead them to understanding and ultimately to self-forgiveness. I’ve been here several times myself since I left my beloved Earth. I can come and go as I wish now that I’ve atoned for my own sins,” my guide says with a wink.

“But I never drank of Lethe’s waters. So my past still lives in me, as do the many words I scribbled into notebooks, now in the hands of libraries and scholars. I mostly find the Underworld’s denizens thoughtful, if sad, beings.”

“Is there a heaven? Do people ever go to heaven?”

“Heaven is a construct of religionists, as is purgatory – both man-made inventions. Can you imagine anything more punishing than an eternity in the company of ‘Godly people,’ a benevolent, all-powerful being, and a choir of seraphim strumming harps?

“The souls in here are working hard to return to Earth. I only pray your generation leaves something to return to. Will you poison yourselves before you destroy your earthly home?”

My guide’s question reverberates in me, the same question that emerged from my research that sent me into such despair.

“Can you imagine a more sacred cathedral than the Northeastern boreal forest, the Midwest great plain and the Southwest desert we traversed coming to this desolate place?

“Although the River Lethe is arid now, the spring from which it used to flow still bubbles up. Satisfying what may be centuries of thirst, all returning sinners stop to drink of its waters and so lose all memory of their time in here. But they retain the lessons of their hard work, becoming better people.

From Canto VII, Homicides & Poisoners

I stare aghast as the endless parade of maimed souls circulates, some crawling, some on crutches, some carried by others, but no one stopping to rest. I see a suicide still wearing the noose and rope from which he was cut down, another with bullet wounds in his skull, yet another whose severed body parts he carries with him under his one arm, another bent over in pain from the bottle of pills he used to kill his wife who hangs limp from his shoulders. The whispered conversations continue. I see a man desperately trying to breathe life into the wife he beat to death in a fit of imagined jealousy as he alternately cries and begs her to come back. I hear afar a mass chorus of ragged shtetl Jews, Poles, and Romany of all ages coming slowly into view as they shuffle together, singing hoarsely Schiller’s Ode to Joy movement from Beethoven’s Ninth symphony, the unliberated revenants of Nazi deathcamps.

I turn away in horror.

Further on a hill farmer slakes the burning thirst of a coal mining executive with black water from a canteen. Napalmed peasants, their skin blistered and rife with boils, converse with helmeted pilots sipping from thermoses. A blind Indian woman, her face distorted by an acid attack for marrying beneath her caste yells furiously at her brother and flails blindly at him. He seems not to notice as her fists flit about his face. A backroom abortionist whose coat-hanger surgeries destroyed the reproductive anatomy of countless women drags a mound of fetuses on a crudely fashioned travois to which he is harnessed. I see suicides trying to hold in between their fingers the organs spilling from self-inflicted wounds. Again, I turn my head away in horror.

From Canto X, Lethe

I’ve taken up walking in the woods again, a source of solace when I’m distraught or lonely.

Deep in the woods of the Green Mountain National Forest, a vast 400,000-acre Vermont wilderness, I can walk for days with only flora and fauna for company and am gradually recovering a sense of purpose beyond my research. Even as the acuity of my senses wanes, I marvel at the sounds, smells, and sights of the forest and its waters. Every walk-about is rife with the vibrancy of natural life I never saw before except in microscopes and test tubes.

In my retirement, I’ve been offered continuing use of the university’s labs to pursue my work and can come and go, pursuing my research as I wish, but my age now limits my rambles to two or three days before I must return home.

On my current trek, I’ve been walking for two days, enjoying the woodland sustenance I find, supplemented by my stores of muesli, dried herring, and raw vegetables. The great pleasure of pine-needle or chaga tea at dusk in front of a small fire evokes confusing memories of my sabbatical walkabout. I camp beneath the overstory of ancient sugar maples where I can see and hear the night flight of owls, woodcocks, hermit thrush, and whip-poor-wills. And through it see the twinkling of stars that imbue me with hope for future generations. I think so often of Flora and wish she were with me here in the forest and we could talk together of all we see and hear.

I’ve spent much of my life learning with and from others and now I’m largely alone. As life ebbs, loneliness affords me the luxury of monologue, and I’m surprised to find how much I learn through self-inquiry.

The culmination of my life’s work in research only affirms my conclusion that, while the exponential advances of science, medicine, and technology have made for a more comfortable world and more time to spend in it — even as many still languish in poverty and disease — the profusion of water, air, and soil-born toxins we’ve invented and loosed on the world have now become a Pandora’s box of man-made ills.