Why is Pharma Obsessed with my Cucumber?

A recent audit report by State Auditor Doug Hoffer lays bare the staggering cost of healthcare to Vermonters – $9,000 per year, almost $2,000 more than the national average. For a worker making Vermont’s minimum wage, that’s over 40% of their gross income of $22,500. The report details many of the drivers of this cost, but nowhere on the list is pharmaceuticals.

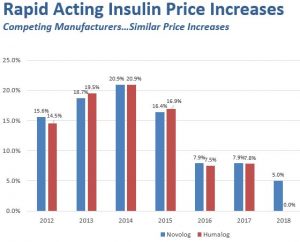

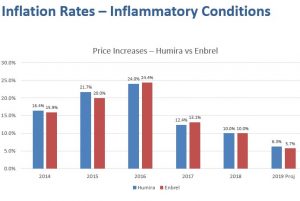

The explosion in Pharma costs and profits is well-documented, tripling between 1997 and 2007, as are examples of price-fixing among competitors as seen in the charts below that were compiled by BlueCross BlueShield of VT and track price changes for two of the most commonly prescribed drugs. There are reasons beyond just greed for such price swings, not the least of which is lack of any significant regulation or oversight.

Deregulation began in 1995 during the Clinton presidency when the industry managed to convince the administration and Congress that it should be allowed to market its prescription nostrums directly to consumers under the rubric of “education” – illegal in most other countries.

Pharma’s big challenge was that most consumers knew little or nothing about the drugs they were given, having always trusted their doctors to prescribe appropriate medications.

Since most prescribed drug names were never familiar to the general public, the industry faced a marketing dilemma. Not only were their drugs outside the vocabulary of most consumers, so were many of the conditions their drugs purported to treat. People’s sense of “wellness” is highly subjective.

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), of the $30B Pharma spent on marketing and “disease awareness campaigns” between 1997 and 2016, roughly one third ($9.6B in 2016) targeted potential patients and half targeted doctors in an effort to induce them to prescribe, all under the rubric loosely described as “consumer and professional education.”

Realizing that many consumers didn’t know they were sick, Pharma set out to market diseases to consumers that they didn’t know they had in an effort to develop new lateral sales of existing drugs.

Early on there was a memorable ad in which a cringing housewife is asked by an authoritative male voice if she gets anxious when going to the supermarket and is told dramatically that she has agoraphobia. The cowering housewife is then instructed to contact her doctor to prescribe Prozac which purports to relieve the condition. The ad also flashes a toll-free number to enable consumers to find a doctor who will prescribe the drug if their own won’t, presumably MDs who have been “educated” by Pharma.

According to JAMA: “Marketing to healthcare professionals by pharmaceutical companies accounted for most promotional spending and increased from $15.6 billion to $20.3 billion (1997-2016), including $5.6 billion for prescriber detailing, $13.5 billion for free samples, $979 million for direct physician payments (e.g., speaking fees, meals) related to specific drugs, and $59 million for disease education.”

In 2005-7, when I chaired the UVM Medical Center (then Fletcher-Allen), I met semi-annually with our several hundred docs to hear their concerns and ask them questions. When asked what constituted the largest waste of their time, the response was uniform… patients’ self-diagnosing based on a drug commercial they had seen on TV that led them to ask for a prescription… “the little blue pill,” or a similar Pharma TV star drug.

Convincing a patient that they don’t have a condition that Pharma has convinced them they have and talking them out of a pill they don’t need that might even be harmful was the major time-waster. If the doctor denied a script, the patient could now simply call the toll-free number on the screen and find a prescriber who had been “induced” to prescribe it.

Having surmounted the challenge of selling a disease and then its treatment, the industry confronted another prickly problem (pun intended). [Trigger warning: some readers may find the following content disturbing, or just funny.]

As a regular reader of three U.S. newspapers, I’m confronted daily with an image of a middle-aged man staring at a curved cucumber. On reading the fine print, I am made aware that the cucumber is a hieroglyph for his curved penis. He has… (drum roll) Peyronies Disease (PD). (Cut back to President Clinton, Paula Jones and Monica Lewinsky.)

In a column that is typically about Vermont, you may ask if this opinion writer has fallen down the rabbit hole?

I raise this issue only to offer an example of how far afield the largely unregulated drug industry has gone, bribing the medical community itself and holding Vermonters and all Americans hostage to its predatory pricing and anti-competitive efforts, such as, when their patents expire, paying vast sums to generic companies not to manufacture cheaper generics (generally called pay-to-delay).

Now that the Sackler family – Purdue Pharmaceutical – has been accused and compared to a drug cartel selling opiates in easy-prey neighborhoods where low income, hard-working folk are subject to stress and pain as in Appalachia and Detroit, museums around the country are grinding the Sackler name off wings, galleries, and special collections financed with their drug proceeds.

But I write because Vermont is part of a federal system and can’t fully control its own destiny. Pharma must ultimately be regulated at the federal level.

Until we Americans make the basic decision about whether healthcare is a basic human right as so many other civilized countries have or merely a product to be sold to those who can afford it, most Vermonters will never be able to afford health security.

Right now, given that Pharma has spent some $5B in the last ten years to influence Congress not to impose regulation, the chances of bringing the industry to heel seem remote.