A Community-Engaged Hospital in Vermont

Photo courtesy of Brattleboro Memorial Hospital

Too often I write about our misunderstanding of the complex systems that plague us and our failure to reimagine them as functional solutions to our many social and economic problems. This column will be different.

I was recently invited to speak and participate in Windham County’s “Windham Aging” conference at Brattleboro Memorial Hospital. Their hospital CEO, Chris Dougherty, and I were kick-off speakers. The invitation was from two of the founding partners of “Windham Aging,” former Secretary of Agriculture and CEO of Grace Cottage Hospital, Roger Allbee and David Neumeister, a retired Brattleboro dentist. Another founder, Dr. Carolyn Taylor-Olson of Brattleboro Memorial Hospital also participated.

Windham Aging’s self-described mission is: “Older Vermonters in Windham County want to be self-determined, connected and fulfilled with health systems of support that work for everyone.”

The day was a learning experience for me. I observed how a community committed to exploring and implementing solutions can find its own way to achieving them with a broad coalition of community partners.

I also learned what a true community hospital could and should look like. I wish every day was as fulfilling as this one was.

It’s been clear for some time that the wellbeing of our aging communities exceeds the capacity of healthcare. It’s more dependent on our commitment to “the common good” than we care to realize. In trying to solve our societal challenges, we tend to focus on the typical silos of housing, food systems, environmental degradation, poverty, public education and healthcare access, but miss how the health of our communities is intrinsic to the health of their inhabitants.

The senior population of Vermont is increasing at a faster rate than almost all other states. A quarter of our population will be over 65 by 2030 as many baby boomers move into their retirement years. The share of Vermonters ages 65 to 79 from 2011- 2019 rose from 10.5 percent to 16.4 percent. This puts us at No. 2 nationally for the percentage of people 50 and older. Only Maine has a higher ratio of seniors, and Vermont is tied for No. 2 with New Hampshire for the highest median age. Windham County is aging even faster than the rest of Vermont. Between 2020 and 2040 the projected increases for ages 60-64 is 38%, age 80-84 is 127%, and 85 and up is 159%.

Meanwhile, a recent Washington Post study indicates we’re going in the wrong direction in dealing with an aging population, while our peers in other countries are making progress. We’re failing at a fundamental mission — keeping people alive. After decades of progress, life expectancy — long regarded as a singular benchmark of a nation’s success — peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years, and then began to drift downward even before the coronavirus pandemic. Among wealthy nations, the United States in recent decades went from the middle of the pack to being an outlier. And it continues to fall further and further behind. This does not suggest we have a sound understanding of, or approach for, extending quality of life into old age.

“Population health” is understood as a system that ensures quality, access, and affordability. Many of our hospitals generally succeed on the quality component ̶ remembering that medicine is both an art and a science and, as such, is subject to human error. But Vermonters daily encounter failures in access and affordability. Too many Vermonters give up on healthcare, fearing they can’t afford it, or struggle to book an appointment and give up. Or they may not have the transportation they need to travel to an emergency room far away. There’s no more expensive or hard-to-access facility than a distant tertiary-care hospital emergency room. Large hospitals should always be the first stop for true emergencies and trauma but the last stop in a well-designed upward referral system based on patient acuity.

As to aging, the social milieu in which we live is a major driver of good or bad health. Don Berwick’s widely accepted social determinants of health (DH) make this clear. They are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes ̶ the conditions in which people are born, grow up, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life, such as social, economic, and political policies and systems, social norms, and even birth zip codes. (It’s a known fact, supported statistically, that a person’s zip code affects their life expectancy more than their genetic code.) With a profound influence on health, levels of income and illness follow a social gradient: the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the health.

Social determinants can also be more important than healthcare or lifestyle choices in influencing health. Numerous studies conclude that they account for between 30% and 55% of health outcomes. Finally, estimates show that the contribution of sectors outside healthcare affecting population health outcomes exceeds the contribution from the health sector.

By way of example, in May, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy issued a sobering advisory on loneliness in American society. He was clear about the serious public health consequences of an increasingly solitary population. Research indicates that the risk of premature death posed by “being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, and even greater than that associated with obesity and physical inactivity.” “I want the entire country to understand how profound a public health threat loneliness and isolation pose,” Murthy added.

Among the community assets that support wellbeing are:

- Community meeting and exercise places in nature, such as parks and biking/walking paths.

- Diverse centers of worship, ritual, and celebration.

- Accessible, affordable public transport.

- Lifelong-learning opportunities for all ages, with opportunities to explore and learn about artistic expression, crafts, and hobbies: painting, dance, choral singing, pottery etc.

- Co-housing opportunities for those who seek or need it.

- Strong local news organizations.

- Communities in which citizens are not segregated by age but can interact socially with young people ̶ opportunities for mentoring, volunteering in daycare, schools, sports, churches etc.

At the conference, break-out sessions included Social Connection, Engagement & Wellness; Disease Management, and Housing and Transportation.

Additional presenters included Angela Smith-Dieng, Division Director of VT Dept of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living, and Rhonda Williams, Chronic Disease Prevention Chief at the VT Dept. of Health.

* * *

But perhaps the highlight of my day was the presentation by CEO Chris Dougherty. I’ve met in the last year with several hospital CEOs and was not expecting the radically divergent view with which he views the role of his hospital in today’s healthcare infrastructure.

Dougherty started off enigmatically by saying, “My job is to minimize the number of people coming into my hospital,” then explaining that when fewer people need its services a hospital is best serving its community. This is achieved by forging deeply rooted partnerships with community organizations that support community wellbeing such as home health agencies, local clinics and primary care facilities, sole practitioners, hospice, EMS, housing agencies, childcare providers and the like. Done right, this community network will ensure the wellbeing of its members and over time fewer of them will need the services of a hospital emergency room.

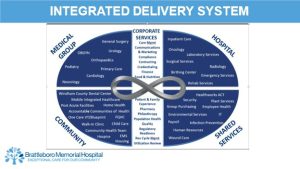

I’m so used to public, nonprofit hospitals focusing on a competitive relationship, expanding both services and infrastructure to accommodate more and more patients and prospective patients and the revenue they bring. Hearing a hospital CEO say that a hospital’s prime responsibility is to partner with community agencies to create an integrated healthcare delivery system to both ensure good health and prevent illness was a surprise, as well as insisting that “it takes a community to elevate the health of the community.” Here is the slide that accompanied Dougherty’s comments.

The contrast between what I’ve heard from several hospital CEOs about their vision for success being tied to market control and expansion and this alternate vision at Brattleboro Memorial Hospital of being the keystone in a collaboration of networked community agencies to create an “integrated healthcare network” was a breath of fresh air. It rang true to the mission-driven objectives of the best nonprofits among us. They collaborate rather than compete.

My time in Brattleboro was like a graduate course in how modern healthcare can succeed with the help of a committed community and a truly nonprofit vision. Our network of hospitals has much to learn from Brattleboro’s vision.

I thank them for inviting me down. I learned so much and look forward to coming back.